Salløv – carved in stone but surrounded with mysteries

On a runestone found at Snoldelev to the south of Roskilde we can find the oldest written form of a place-name that can with certainty be linked to a place in present-day Denmark. The brief runic inscription, however, gives rise to many questions and speculations.

Runic inscriptions are the oldest contemporary source for the language that was spoken at the locality in the Iron Age and the Viking period. The Danish place-names can already have been formed before the runic inscriptions were carved, and many of the names were formed in the same period, but mostly they have only survived in younger sources from the Middle Ages, where they were written down in Latin letters.

In spite of the fact that they have most often been written down several centuries after their formation, place-names are a copious source for the vocabulary employed in prehistoric Denmark – or rather what became Denmark in a period that is difficult for us to delimit.

An example of a place-name that with reasonable certainty was formed in the Iron Age is Snoldelev, which today is the name of a minor settlement situated on the island of Sjælland approximately halfway between Roskilde and Solrød Strand. Snoldelev is both the name of the village and the parish and it is formed from the otherwise unknown masculine forename Snāldi and the more familiar second element -lev, which means 'something that has been left behind' or 'hereditary estate'. It is generally assumed that names in -lev were formed at some time between 300 and 800, and since the name has not actually been recorded before about the year 1300 as Snaldelewie on a tombstone in Roskilde Cathedral, about 500-1000 years can have passed between the formation of the name and the earliest written form we have today.

The Snoldelev-stone

Not far to the west of Snoldelev there lies another settlement called Salløv. This name is of particular interest because it is one of the very few Danish place-names to be named in a runic inscription. It might look as though the place-name Salløv also had the ending -lev but this is not the case. We shall return to this later.

The runestone is called the Snoldelev-stone (and not the Salløv-stone) because the stone is named after the parish where it was found. It was discovered in 1780 in a rather stony area between Salløv and Snoldelev. Much younger archaeological investigations at the site have shown that there was a burial place, where among other items there was found the rich grave of a woman dating to the early Viking period.

There are differing traditions for how one divides the prehistoric periods: Archaeology normally places the limit between the Iron Age and the Viking period to approximately the year 800. Runologically the new runic alphabet or futhark with only 16 symbols, as opposed to the 24 symbols of the old alphabet, marks a fixed point in time. The oldest inscription that can be dated with any certainty as using the 16-symbol alphabet is an inscription on an amulet from Ribe dated to about 725/50. Therefore the Viking period in runological opinion is taken to begin at that time.

The inscription on the amulet from Ribe contains some rune forms that graphically really belong to the old runic futhark, namely the symbols ᚺ og ᛗ (for respectively H og M) as well a special a-rune ᚼ which only occurs in this transitional period. The runic symbols ᚼ and ᚺ (A and H) are also employed in the Snoldelev-stone's inscription. It is reasonably certain that the old symbol ᛗ (M) was employed in a bent form of the place-name Salløv. How all this information is to be tied together will be discussed below.

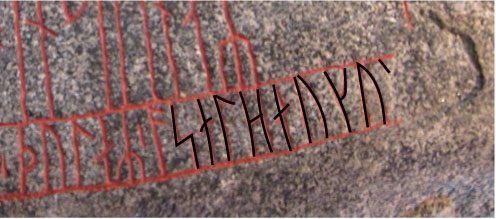

The falling together of the notations between the two futharks shows that the inscription on the stone can be considered to be contemporary with the one in the amulet and that it must therefore date from the early Viking age, that is approximately the years 700-800. The Snoldelev-stone is now exhibited in the National Museum and a copy of it has been placed in Sagnlandet Lejre. In addition to the runes there are three symbols carved on the stone: a triskelion (which is perhaps a representation of interlaced drinking horns) and the astrological symbols a swastika and a wheel cross. The inscription and the symbols have been painted up with a red colour except for the indistinct wheel cross that can just be distinguished above the triskelion, on top of which the inscription has been written. The stone must therefore have been re-used.

What does it say then?

All the symbols in the inscription are readable with the exception of the very last one. In pictures it is clear to see that something has been lost. Rune stones are often more porous where they have been carved and it is sometimes possible to follow the lost text as a shadow from the framing lines. Inscriptions on rune stones are almost always either vertical or follow the contour of the stones and the inscriptions most often begin at the bottom on the left. It is almost only King Harald's Jellinge-stone that has horizontal lines, probably as a reference to the book-culture that had then not yet been introduced in Denmark. A symbol of modernity and foresight.

The Snoldelev-stone's inscription is carved over two vertical lines, both framed in but not equally large. Prominent is as always the name of the person about whom it concerns. It is first and foremost personal names that we meet in runic inscriptions. It must have been less important at that period to know where the influential members of society lived or were staying – with the exception of Gunvald or Roald, who are named in the inscription on the Snoldelev-stone, which is shown as follows:

Transliteration into Latin characters

kun:uAltstAin : sunaR : ruHalts : þulaR : ą salHauku-

Normalisation to runic Danish:

Gunnvalds stæinn, sonaR Hrōalds, þulaR ā haugu(m)

Normalisation to modern Danish:

Gunvalds sten, søn af Roald, tul på Salhøje(ne) (Salløv)

In modern English:

Gunvald's stone, son of Roald, wise man (þulr) at Salhøje(ne)

The wise man at Salhøjene

The inscription reveals that Gunvald was the son of Roald. One of these two men must have been the wise man at Salløv but the grammar in the inscription does not reveal which of the two was the wise man. The precise meaning of the word 'þulr' in the early Viking period is questionable but it is certain that the word is to be linked with the Old Icelandic word þulr that means 'speaker', 'wise man' or 'poet'. Whoever read the inscription in the early Viking period would certainly have known both which of the two was "þulr" and exactly what that involved. In Eddic poetry the term þulr is associated with the cultivation of heathen worship and there may be something to be learnt from the place-name Salløv.

As already mentioned the final letter in the place-name has been chipped away and this is probably an M-rune with the form ᛗ but why should there have been an m in the name Salløv? The explanation lies with Danish grammar in the early Viking period.

The language was one with cases, as found in, for example, German and Latin. A way in which the cases can be seen in both Modern German and Old Danish is in the use of the combination preposition plus substantive, where the substantive that is inflected is given a particular ending. Which case is used depends on the preposition. In Modern Danish there are still some examples of old fixed forms of substantives governed by prepositions, e.g. til bords (genitive) and fra borde (dative). The substantives could also have one of three different genders: masculine, feminine or neuter. In the Middle Ages these were gradually reduced to two genders because masculine and feminine fell together to one, namely common gender. Substantives could also, just as today, be declined as singular or plural.

The runic sequence ą salHauku- consists of a preposition ą (Old Danish á) that means 'at' , followed by a name with two elements sal and hauk and an inflectional ending u-. The word sal corresponds to the modern word sal which today means 'large or fine room'. The diphthong [au] in hauk develops to (long) [ø] in East Nordic (Danish and Swedish), the k-rune (ᚴ) can stand for g. Therefore hauk can be reconstructed to the Old Danish form høg, identical with the modern substantive høj 'hill'. In Norwegian and Swedish this word still has a g-pronunciation but already in the Middle Ages the pronunciation has been weakened in Danish, reflected, for example, in the spelling høw. It is this development that is concealed in the modern form in -øv in Salløv. The second element is thus not an old -lev but a form of the substantive høj 'hill' as in old place-names that mean 'burial mound'.

After the preposition á that means 'at' the following word or name will always be declined in the dative case. There is a fixed pattern for the inflectional suffixes in the dative. In the singular the ending can be -i (masculine and neuter) or -u (feminine), in the plural the ending is always -um in all three genders. The substantive høj is masculine and has always either a dative form in -i (singular) or a dative form in -um (plural). The surviving part of the case-ending is a u and it is therefore necessary to conclude that the element høj must have had a dative plural in -um. The form must be reconstructed salHaukuM (normalized to Salhøgum) and the runic sequence ą salHauku- must be translated as "at the mounds with the great man's house”.

The significance of the houses

The word sal also occurs in other old place-names, e.g. in Salby near Kerteminde, Lille/Store Salby west of Køge and in the simplex names Sahl and Sall between Viborg, Randers and Silkeborg. As well as in Norwegian and Swedish place-names. There has been much discussion as to what the word means as an element in place-names and scholars have linked it with meanings such as 'heathen cult place', 'hall' and 'magnate's residence' but also with much less elite meanings such as 'temporary residence', 'booth' or 'cattle shed'.

It is probably the case that the word can have different meanings as a place-name element but that it always deals with some form of accommodation where human-beings or animals can be kept, perhaps particularly in connection with special occasions. In the interpretation of the name Salløv the "tul” mentioned on the stone and the conceptions of such a person's cultic position in society has influenced the cultic interpretation as "heathen temple”.

No trace has been found of such a special building but considering how seldom place-names are included in runic inscriptions it is not unlikely that there was a particular function and history associated with the place-name in the time of Gunvald and Roald. On a scientific, linguistic basis one can hardly get any closer to an interpretation, but a guess might be that the gravemounds at the cemetery were imagined to be halls or rooms, perhaps with the meaning temporary accommodation for the dead before their departure to the kingdom of the dead.

Rikke Steenholt Olesen

Contact

Rikke Steenholt Olesen is associate professor at the Name Research Archive, Department of Nordic Studies and Linguistics

rikke.steenholt.olesen@hum.ku.dk

+45 3532 8564